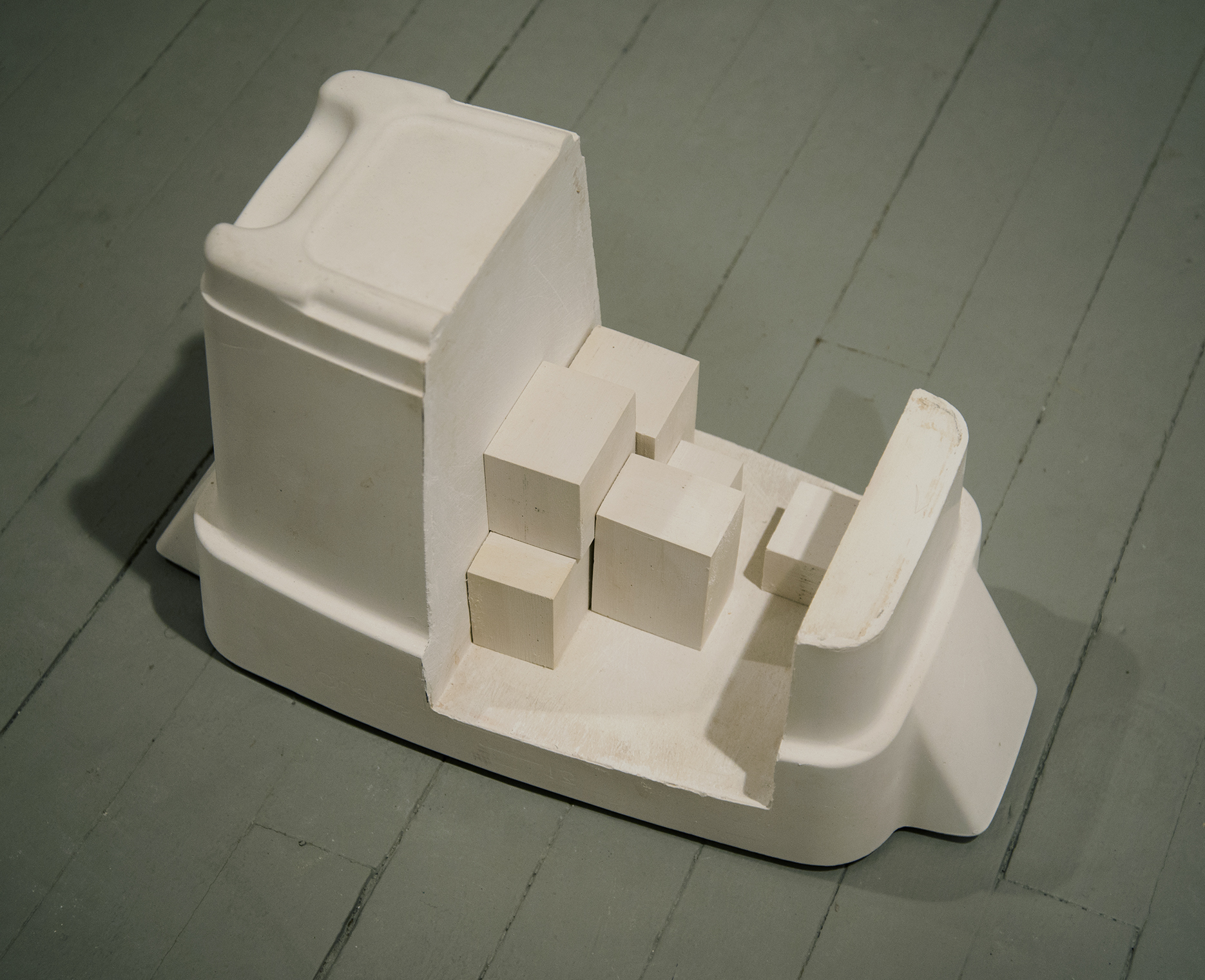

Stux Gallery, Boston MA 1982

cast plaster

Based on Heidegger’s famous analogy of the bridge, the barely suggested characteristics of courtyard, axis, and ambulatory already present in the gallery are completed with the insertion of large cast plaster blocks that form doorway (to receive the axis from the gallery entrance), low wall (to complete the implied courtyard), and sarcophagus-like center structure (to force ambulation around the form).

A Courtyard, an Axis, An Ambulatory

THE BOSTON PHOENIX, January 28, 1982

By Kenneth Baker

The key to Jeffrey Schiff’s installation at the Stux Gallery, on the Newbury Street (though January 30), is a quotation from Heidegger that sits alongside the artist’s biography on the window ledge. The quotation is one of the most famous passages from his late writings; in it he asserts that the banks of a river come into being as banks only in the presence of a bridge connecting them.

Schiff apparently intends his installation to be the bridge to the gallery structure’s banks. The show has three components; they’re assembled with cast plaster blocks, and Schiff calls them “A Courtyard,” “An Axis,” and “An Ambulatory.” As physical units, the modularity and individual identity. There is a pleasing dissimilarity between the most regular of them and those that are notched to fit closely under the window ledge or against the baseboards.

The three structures that form the installation are about as similar and as different as their elementary components, at least formally. But the “Axis,” which mirrors the gallery entrance, is a weak link in the show. The two floor pieces are much more effective in their restatement of the spatial dimensions of the gallery.

In looking at work like Schiff’s, it is worth remembering that the physical structure are not ends in themselves but devices intended to focus our attention on certain varieties of experience that might otherwise elude us Ð varieties of experience that might not even exist. The partial closure of the windowed end of the gallery with low plaster slabs (“A Courtyard”), for instance, enables us to feel the openness of that space in a way that is simply not possible when the gallery is as open as it can be. Similarly, the “Courtyard” makes us aware of the daylight entering the windows as a force that gives the space its character; it achieves this by forming an open container into which we can sense daylight falling. These observations naturally make us more aware of the gallery’s artificial light: we see its artificiality more clearly. Parallel observations could be made about the effects of the “Ambulatory” on the other end of the gallery, which is narrower and windowless.

Schiff’s work presupposes our interest in subtleties of experience and physical awareness. It is not oriented toward consumption but toward reflection, and for this reason many will likely dismiss it as “conceptual” or simply empty. But one reason people resort to such dismissals, apart from impatience and the habit of consumption, is to avoid the kinds of experience that works of art can provide us about ourselves, to avoid seeing and thinking beyond the crude categories we ordinarily use to orient ourselves. It is difficult to judge work like Schiff’s in terms of success or failure Ð too much depends on our willingness to exert the critical energy the artist requires. You will probably like or dislike the work less for its physical and visual character than for its affinity with your idea of what should be done with art by those who look at it.