1986-93

Sculpture Center, New York, NY 1993Jeffrey Schiff’s devices center on the psychologically resonant physicality of the tool. Their formal elegance suggests careful design rather than ad-hoc ingenuity. This leads one to expect that these objects, as well-made tools, will be intelligible in terms of some underlying purpose. Instead of being stable images or representations, they act as catalysts for speculative scrutiny. As one attempts to work out their purpose, it becomes clear that these singular objects have a multiplicity of ways and meanings. They trigger an investigation which can never be satisfactorily concluded. The tools are themselves work sites — work sites for interpretation.

Sculpture Center, New York, NY 1993Jeffrey Schiff’s devices center on the psychologically resonant physicality of the tool. Their formal elegance suggests careful design rather than ad-hoc ingenuity. This leads one to expect that these objects, as well-made tools, will be intelligible in terms of some underlying purpose. Instead of being stable images or representations, they act as catalysts for speculative scrutiny. As one attempts to work out their purpose, it becomes clear that these singular objects have a multiplicity of ways and meanings. They trigger an investigation which can never be satisfactorily concluded. The tools are themselves work sites — work sites for interpretation.

- Grinder (3’x4’x4′) cement, wood, steel

- Forge (1.5’x2.5’x2.5′) lead, steel, wood

- Carted Block/Blocked Cart (3’x2.5’x1.5′) granite, steel

- Vat 27″x27″x27″ steel, beeswax

- Vat-detail

- Re/past Table (29″x59″x40″) concrete, wooden table

- Re/past Table-detail

- Scribe (7’x10.5’x1.5′) felt, steel (Collection San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art)

- Scribe-detail

- Field of Influence (7’x8’x4′) felt, steel, stone

- Field of Influence

- Estate (90″x66″x3″) felt, steel, lock

- Opening Up 3.5’x4’x2.5′ concrete, steel. carbonendrum (Collection San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art)

- Opening Up-detail

- Garden Path (1’x12’x5′) steel, fieldstone, casters

- Cast-Out (7’x8’x12′) steel, wood

- Cast Out

- Advance Notice (6’x9’x9′) steel, wood, sea sponge

- Universal Set 9′ high wood, steel

- Fingers (8′ high) steel, rubber, house-plant

- Ornamental Instrument (4’x4’x5′) steel, steel cable, wood

- Locator (60″x40″x35″) steel, lead, wood

- Loops (8’x4’x2′) rope, steel, wood, paint

- Rope Handles-detail

- Sieve Piece

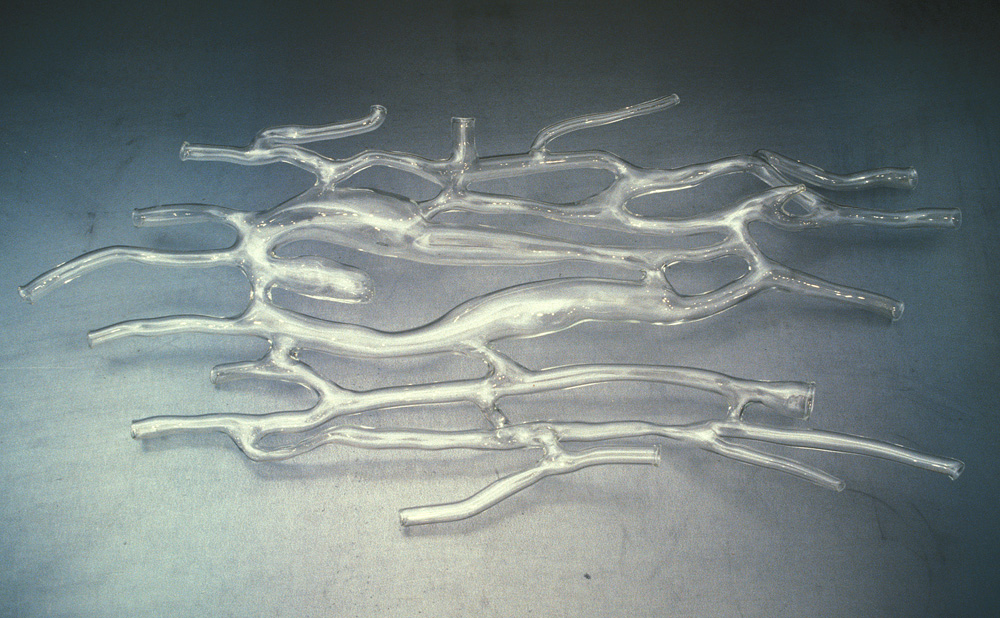

- Sponge Tube